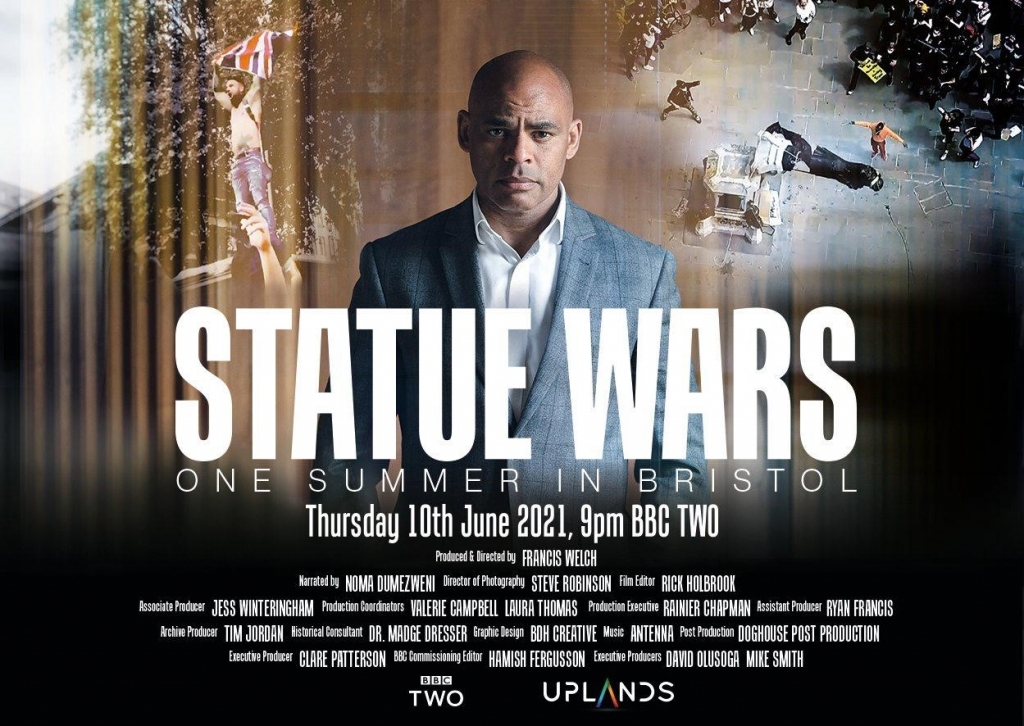

Why the fall of Colston isn’t the knockout blow for racism … yet.

With the removal of a controversial statue of slave trader Edward Colston during a Black Lives Matter demonstration in May, Bristol has become a focal point of a global movement that is taking a stand against racism and systemic injustice.

With the removal of a controversial statue of slave trader Edward Colston during a Black Lives Matter demonstration in May, Bristol has become a focal point of a global movement that is taking a stand against racism and systemic injustice.

However, the empty plinth that stands in the city’s centre is a poignant reminder to Bristol’s citizens that a defiant stand must be followed by concrete action. In order to transform a city which still remains one of the most unequal in the UK, the focus at Empire Fighting Chance remains on improving the opportunities for and wellbeing of young people whose lives still remain blighted by poverty, deprivation and injustice long after the dust of Colston has settled. This week, the quick removal of a powerful but unauthorised replacement work show that for much of Bristol work still needs to be done to decide on the cities future direction.

“Racism isn’t fixed in Bristol” says Martin Bisp, cofounder of EFC, a prestigious boxing gym who are now a vital mental health service for some of the cities most marginalised communities.

“What this has done is remove a statue of somebody who shouldn’t have been being celebrated and that was offensive to many people in Bristol. Has it meant that the young people we work with have got more access to jobs? Does it mean they are living in a more equal society? I would say not. Just because the statue is no longer there, that doesn’t mean that the attitudes or the systemic problems have gone away.”

Martin Bisp, CEO Empire Fighting Chance

Marvin Rees, the first directly elected Black mayor of a European city and ambassador for EFC, explains that “we have major race and class fractures within Bristol that are quite historic. Inequality in Bristol is stark, we’ve got all this wealth but we’ve also got 6 areas that are in the top 1% of the most deprived in England. We have about a 9 year life expectancy difference between the richest and poorest. Bristol West has amongst the highest number that go off to higher education, Bristol South has amongst the lowest. Racism is not just about individual attitudes, racism is about the everyday structural inequalities.”

Based in Easton, one of the city’s most diverse and deprived boroughs, EFC are well-placed to know how these inequalities impact upon everyday lives. Despite being just 1.5 miles from the affluent city centre and Colston’s now bare base, Bisp says that the young people who come through EFC’s doors are some of the most vulnerable. “We work with the local community because we are a part of it, it is around 43% BAME, and we work with some of the poorest and most vulnerable young people in the entire country. Sadly as things stand in Bristol, according to the Runnymede report, the social mobility is the least of anywhere so if you are born poor in Bristol, you are likely to die poor”. Co-founder Jamie Sanigar says the effects of this on young people can be devastating.

“We are dealing with young people that maybe can’t afford clothes, can’t afford shoes, that are hungry” he says, “there is nothing for the young people, and it is destroying their self esteem.”

Jamie Sanigar, Co-Founder Empire Fighting Chance

EFC offer a bespoke package of support designed to begin to break this cycle of systemic disadvantage that in most circumstances young people have been born into. EFC’s unique programme of mentoring, therapy, careers advice, job placements and education was described by as a “one stop shop for help and support”. It is built around a twenty week non-contact boxing programme designed to make long term differences to a young persons mental and physical health and also to improve their self belief, providing them with opportunities for long term change.

“You have to overcome a lot of barriers to get your seven GCSES. If you come from a disadvantaged background, it’s much much harder than if you come from a well educated, middle-class background. What we do is we put them in front of tangible, real-life role models. We give them the skills to be able to aim higher. We talk about aspiration; we put them in positions where they can achieve”, says Bisp. “There is a whole, systemic lack of opportunity and then a lack of aspiration caused by the fact that there is nobody in their community that has done it. A victory for us is a kid going back to school and staying in school - we want to give them the best possible chance of succeeding in life. That achievement could be anything: we don’t care if they are a brain surgeon or they sweep the road, as long as they find something that they find fulfilling.”

Over the last 14 years, the programme developed by EFC has used boxing’s grittiness and appeal to working class communities to provide support to people who would not otherwise access mental health or careers services, with a proven track record of success. Rees says traditional therapy is too often “a middle class service for middle class people” which is inaccessible to the vast majority of Bristol’s diverse communities. Of the 4225 young people EFC worked with in 2019, 74% are no longer at risk of exclusion from school, 86% are more confident and 90% have progressed into employment, training or further education. However, despite these successes, EFC are keen to point out that there is much more to be done and want the fall of Colston to be the start of a new chapter and not a full stop.

“What we’re hoping is that the statue coming down…has made this conversation a little more open. By directly addressing some of the disadvantages that these young people have got, we’re hopefully making life a little bit easier for them and starting to include parts of the city in this discussion that may not have been involved. What we all need to do now, is rebuild, create opportunities and be more open and honest with each other; looking at the bits we need to improve and seeing what we can do to make a difference. Sometimes it takes this type of symbolism to open peoples eyes to a wider issue.”

Martin Bisp, CEO Empire Fighting Chance

For now, EFC continue to take referrals of young people in need of strong, motivated and experienced support team from schools, charities and organisations across Bristol and South Wales. “We’ve never turned anyone away, if you need support we are here for you”, says Bisp.

Written by Alex Turner